True Friendship

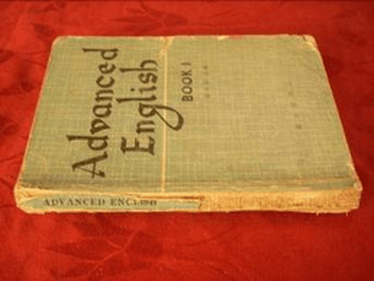

In my debut novel, Revolution is not a Dinner Party, there is a scene where Ling, the main character, watches her father burn the family’s books and photos. This actually occurred in my childhood. My father, a prestigious surgeon trained by American missionaries, destroyed all his beloved books to protect our family from the zealous Red Guard. Yet he continued my education in secret, which included English lessons, a dangerous violation. He instilled in me a love for books and a yearning for freedom. During the Cultural Revolution, the only books we were allowed to read were Mao’s teaching and government-approved propaganda that praised the Communist philosophy. Everything else was banned and burned.

The few good books that escaped the flames formed the basis of an underground library. To be invited into one of these lending networks was a sign of great trust and true friendship. Any careless conduct would bring enormous risks to everyone involved. Punishment could include hard labor, jail, or public humiliation. Parents often received harsh punishment on behalf of their “seditious” children. When I was fortunate enough to acquire an underground book, I would keep stacks of government newspapers and propaganda pamphlets nearby. In the event of an unexpected visitor, I could quickly hide the book among them.

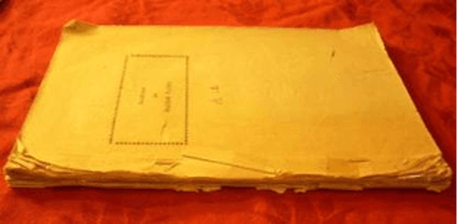

Each time a good book became available, word quickly spread through the small underground group. After working out the order, we would pass the book discreetly among us. When it was my turn, I never felt there was enough time to finish a book in the day or evening allotted to me. I often wished I could read it over and over.

The books we read had passed through many hands. They were often missing pages, usually in the beginning or the end. We spent hours arguing over what happened in the lost sections. That was when I decided to write my own versions and pass them along with the incomplete books to the next borrower. I often wonder, if I had not grown up reading books with missing pages, would I be a writer today?

Each time a good book became available, word quickly spread through the small underground group. After working out the order, we would pass the book discreetly among us. When it was my turn, I never felt there was enough time to finish a book in the day or evening allotted to me. I often wished I could read it over and over.

The books we read had passed through many hands. They were often missing pages, usually in the beginning or the end. We spent hours arguing over what happened in the lost sections. That was when I decided to write my own versions and pass them along with the incomplete books to the next borrower. I often wonder, if I had not grown up reading books with missing pages, would I be a writer today?

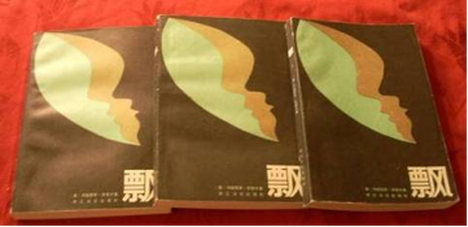

After Mao’s death, the Chinese translation of Gone with the Wind emerged in a small quantity, published as a set of three volumes. When I found out that one of the boys in our group had a complete set, I traded my copy of Robinson Crusoe and half of Jane Eyre (the other half had been torn up by the Red Guard) for the first two volumes. I had nothing to trade for the third, so for weeks I waited for my turn.

During Mao’s reign, everyone was required to wear dark blue uniforms. After his death, few families had enough money to buy what seemed like frivolous new clothes for their children. I was among the few lucky girls in our neighborhood that owned a dress, while my girlfriend had never worn one. Desperate to find out what happened to Scarlett O’Hara, when her turn came first, I struck a bargain with her. I offered to lend my precious new (and only) homemade dress. In exchange, she agreed to let me read the third volume with her. She was allowed to keep the book from dusk to daybreak.

That evening, I anxiously waited for her at our door. She arrived after my parents left for their night shift at the hospital. Once inside, she carefully took out the worn copy from under her shirt, where she had hidden it from the hungry eyes in the courtyard. The electricity to our apartment was cut off at night to power the factories that had been idle during the Cultural Revolution. Lamp oil was still rationed, so we read the book by dim candlelight. When that burned out, we stood before my bedroom window, struggling to read by the faint street light. She was a much faster reader, and had to wait for me to catch up at end of each page. After hours of standing, we were so exhausted we took turns lying down and reading to each other. We finished the book as the first rays of light colored the sky. She left, wearing my dress, just before my mother returned from her shift.

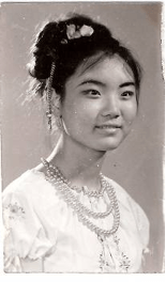

A few days later, she showed me a portrait of herself smiling broadly in my dress, wearing colorful costume jewelry borrowed from someone else. One of the popular things for girls to do during those times was to loan each other our best clothes and jewelry and then get our portraits taken.

A few days later, she showed me a portrait of herself smiling broadly in my dress, wearing colorful costume jewelry borrowed from someone else. One of the popular things for girls to do during those times was to loan each other our best clothes and jewelry and then get our portraits taken.

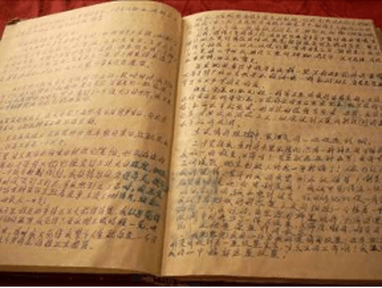

My hunger for good books grew as I matured. I started to copy my favorite passages into a small notebook. When I had nothing to read, I re-read the scribbled paragraphs over and over. Soon, other friends began making copies of their favorite passages as well. Since each of us had our own favorite selections, we would trade notebooks when there was nothing else to read.

My secret forays into these precious books were among the happiest moments in my childhood. They gave me a window to the fascinating outside world, allowing me to temporarily forget the constant hunger and danger. They gave me hope and fueled my dreams.