Ghosts to My Rescue

While I was writing A Banquet for Hungry Ghosts, I frequently wondered if at some time every child has fantasized about having a powerful ghost come to their aid. The brightest light in my childhood was torn from me when, at the height of the Cultural Revolution, my father was imprisoned for the “crime” of being a Western-trained surgeon. His act of loyalty, choosing to stay and help build a new China, was met with punishment. I was categorized as bourgeois, and attacked by working-class children at school.

Always hungry and often scared, I dreamt of mighty ghost companions coming to my aid and exacting righteous revenge upon my enemies. My ghosts’ mystical powers would protect me and punish my tormentors. Or even better, they could just magic me away to a distant, happy place. Those fantasies planted the seeds of my fascination with ghosts and supernatural powers.

Though I embraced ghost stories as a young girl, the Chinese government did not. During the Cultural Revolution, the Communists strictly forbade any form of fantasy or escapist literature, particularly the ghost and fairy tale genres. They didn’t want anyone to believe that ghosts or magic might exist. Yet a long and rich oral tradition remained, despite the ban. Adults used scary ghost stories to entertain, and discipline unruly children. We were told the ghosts would punish misbehaving children. My young friends elaborated upon ghost stories they’d heard to impress or intimidate each other.

From the little I know, in Western popular culture, ghosts tend to stay in one place and don’t obsess over food. In contrast, Chinese ghosts roam about freely, both indoors and out. In some stories ghosts are a symbol of justice, a spirit returned from the dead to right a terrible wrong. Others are destructive and evil. The ones who died hungry are the most menacing.

The imaginary, vengeful ghosts of my younger days became the basis for many of the characters in Banquet. I was delighted by how readily one jumped into Banquet and came to my aid in the last story “Eight Treasure Rice Pudding,” resolving a problem I had grappled with for a long time.

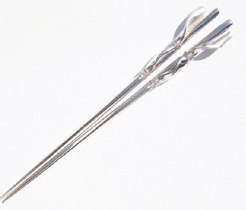

Years ago, I was invited to teach for a semester at Beijing International University. During an outing to the Forbidden City, I learned that in ancient times, the emperor, along with the rich and powerful, would eat with silver chopsticks as a way to detect poison. Arsenic, the poison of choice back then, would react with the silver, turning the chopsticks black.

Years ago, I was invited to teach for a semester at Beijing International University. During an outing to the Forbidden City, I learned that in ancient times, the emperor, along with the rich and powerful, would eat with silver chopsticks as a way to detect poison. Arsenic, the poison of choice back then, would react with the silver, turning the chopsticks black.

The concept fascinated me and I attempted on numerous occasions to write stories about the murders of emperors and silver chopsticks. Despite my best efforts, all the stories rang flat, with shallow characters and a meandering plot. During my last trip to China, I met some friends for dinner in Shanghai, two of whom were fathers of teenage sons preparing for the University Entrance Exam. They expressed their disappointment and frustration with their sons’ performance. I was taken aback when they talked openly about the physical punishment they imposed on their sons when they came home with bad grades.

As I was writing Banquet, the idea of using silver chopsticks as a poison detector resurfaced in my mind. This time, with the aid of a ghost, I was able to parallel the grueling preparations of contemporary University entrance exams with the ancient Imperial Exam. It helped me reveal the age-old conflict between the Chinese father and son—high expectations, disappointment, anger and even hatred—which has permeated filial relationships throughout history.

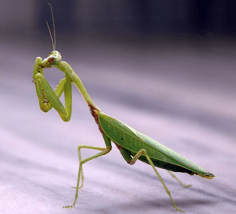

Most importantly, the ghost allowed me to subtly showcase some aspects of Chinese culture which fascinate me: fierce praying mantis competitions, the intricate and rigid traditions of tea manufacturing, and of course, the use of silver chopsticks as poison detectors.

At the end, the tale of a ghost accompanied by a traditional dessert, Eight Treasure Rice Pudding, was a far more entertaining way to bring the story of silver chopsticks to life than a paranoid emperor.

I believe it’s a combination of history, literature and cuisine that lets us truly understand a culture and its people. By using food and ghosts as metaphors, I hope to entice my readers to learn more about China and gain a better understanding of life there, both in the past and present.

Always hungry and often scared, I dreamt of mighty ghost companions coming to my aid and exacting righteous revenge upon my enemies. My ghosts’ mystical powers would protect me and punish my tormentors. Or even better, they could just magic me away to a distant, happy place. Those fantasies planted the seeds of my fascination with ghosts and supernatural powers.

Though I embraced ghost stories as a young girl, the Chinese government did not. During the Cultural Revolution, the Communists strictly forbade any form of fantasy or escapist literature, particularly the ghost and fairy tale genres. They didn’t want anyone to believe that ghosts or magic might exist. Yet a long and rich oral tradition remained, despite the ban. Adults used scary ghost stories to entertain, and discipline unruly children. We were told the ghosts would punish misbehaving children. My young friends elaborated upon ghost stories they’d heard to impress or intimidate each other.

From the little I know, in Western popular culture, ghosts tend to stay in one place and don’t obsess over food. In contrast, Chinese ghosts roam about freely, both indoors and out. In some stories ghosts are a symbol of justice, a spirit returned from the dead to right a terrible wrong. Others are destructive and evil. The ones who died hungry are the most menacing.

The imaginary, vengeful ghosts of my younger days became the basis for many of the characters in Banquet. I was delighted by how readily one jumped into Banquet and came to my aid in the last story “Eight Treasure Rice Pudding,” resolving a problem I had grappled with for a long time.

Years ago, I was invited to teach for a semester at Beijing International University. During an outing to the Forbidden City, I learned that in ancient times, the emperor, along with the rich and powerful, would eat with silver chopsticks as a way to detect poison. Arsenic, the poison of choice back then, would react with the silver, turning the chopsticks black.

Years ago, I was invited to teach for a semester at Beijing International University. During an outing to the Forbidden City, I learned that in ancient times, the emperor, along with the rich and powerful, would eat with silver chopsticks as a way to detect poison. Arsenic, the poison of choice back then, would react with the silver, turning the chopsticks black.

The concept fascinated me and I attempted on numerous occasions to write stories about the murders of emperors and silver chopsticks. Despite my best efforts, all the stories rang flat, with shallow characters and a meandering plot. During my last trip to China, I met some friends for dinner in Shanghai, two of whom were fathers of teenage sons preparing for the University Entrance Exam. They expressed their disappointment and frustration with their sons’ performance. I was taken aback when they talked openly about the physical punishment they imposed on their sons when they came home with bad grades.

As I was writing Banquet, the idea of using silver chopsticks as a poison detector resurfaced in my mind. This time, with the aid of a ghost, I was able to parallel the grueling preparations of contemporary University entrance exams with the ancient Imperial Exam. It helped me reveal the age-old conflict between the Chinese father and son—high expectations, disappointment, anger and even hatred—which has permeated filial relationships throughout history.

Most importantly, the ghost allowed me to subtly showcase some aspects of Chinese culture which fascinate me: fierce praying mantis competitions, the intricate and rigid traditions of tea manufacturing, and of course, the use of silver chopsticks as poison detectors.

At the end, the tale of a ghost accompanied by a traditional dessert, Eight Treasure Rice Pudding, was a far more entertaining way to bring the story of silver chopsticks to life than a paranoid emperor.

I believe it’s a combination of history, literature and cuisine that lets us truly understand a culture and its people. By using food and ghosts as metaphors, I hope to entice my readers to learn more about China and gain a better understanding of life there, both in the past and present.